By Leah Schulz, D.D.S.

From the Spring 2021 Journal of the Colorado Dental Association

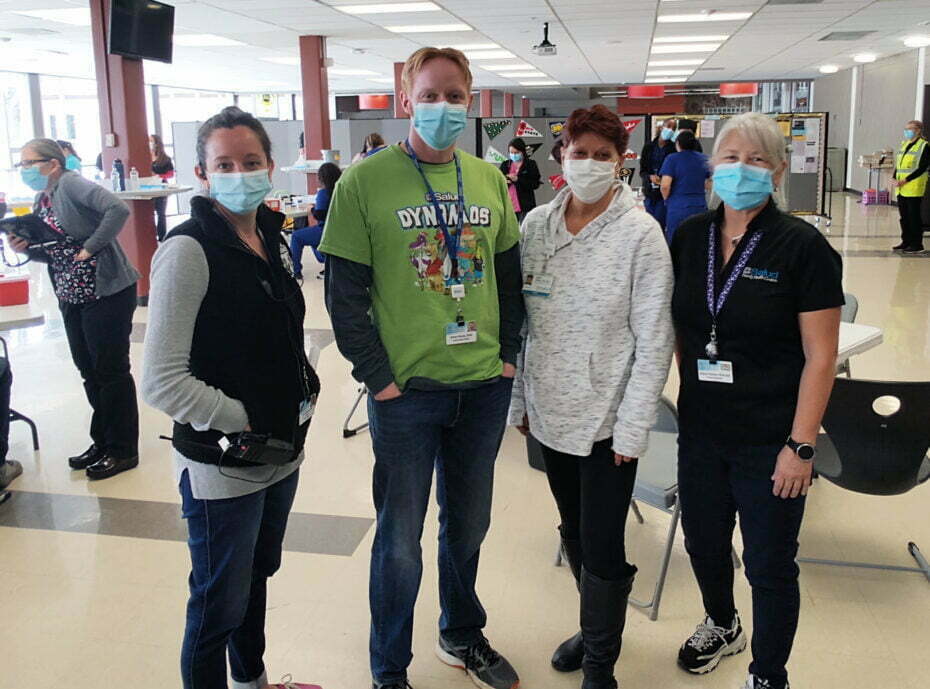

Dr. Leah Schulz (right) administers a vaccine at an 1,800-dose clinic in Thornton, CO.

Like many of you, I’m a general dentist. Up until recently, most days I provided full-scope dental care to patients of all ages and precepted dental students and residents at Salud Family Health Centers (Salud). Salud is a Federally Qualified Health Center (FQHC) that offers co-located, integrated medical, dental, behavioral health, and pharmacy services to historically underserved people, regardless of their ability to pay. Part of the joy of this practice model is that dental teams frequently work alongside other healthcare disciplines to promote patients’ overall wellness, not just oral health.

Consistent with this interdisciplinary approach, my chief dental officer asked me to take a pause from clinical dentistry in early January and shift my focus to help Salud coordinate COVID-19 “pop-up” vaccination clinics that prioritize access for racial and ethnic minority populations, and low-income communities. Although it was a difficult decision to temporarily stop practicing and engage in an unfamiliar public health space, I recognized the incredible opportunity to actively address the greatest public health crisis of our time. So, I dusted off my project management skills and accepted this temporary role. How difficult could this really be? I thought. FQHCs are pros at vaccination!

I can now say after eight weeks on the job that this was tougher than I originally thought it would be. Managing the complex variables at play to deliver a comprehensive, efficient rollout of the COVID-19 vaccine administration to Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC) as well as low-income communities has turned out to be the work of the entire Salud team, dentists included!

It is well documented that BIPOC communities experience higher rates of COVID-19 cases, hospitalizations, and deaths, as compared to non-ethnic white communities. This trend is due in large part to underlying “health status, housing arrangements, transportation use, occupational exposure, and other social factors”.[1]

| Rate ratios compared to White, Non-Hispanic persons | American Indian or Alaska Native, Non-Hispanic persons | Asian, Non-Hispanic persons | Black or African American, Non-Hispanic persons | Hispanic or Latino persons |

| Cases1 | 1.9x | 0.7x | 1.1x | 1.3x |

| Hospitalization2 | 3.7x | 1.1x | 2.9x | 3.2x |

| Death3 | 2.4x | 1.0x | 1.9x | 2.3x |

Race and ethnicity are risk markers for other underlying conditions that affect health including socioeconomic status, access to health care, and exposure to the virus related to occupation (e.g., frontline, essential, and critical infrastructure workers).

Based on the first six months of 2020, the average U.S. life expectancy for non-ethnic white men and women dropped by 0.8- and 0.7-years, but black males experienced a three-year drop, while black females and Hispanic males experienced 2.3- and 2.4-year declines, respectively.[3]

FQHCs, like Salud, are well positioned to act in response to these appalling statistics, since we have been working steadfastly for over 50 years to address health and outcome disparities. As of early March 2021, Salud had already given over 25,000 doses of the COVID-19 vaccine, and by the time you’re reading this that number will have grown substantially. Administering a vaccine was not new to us but developing and implementing a custom vaccine access plan for the needs of our communities has required an innovative, all-hands-on-deck response. Vaccinating these communities has come with its own, unique set of challenges.

For starters, a history of systemic “medical racism”[4] has created a distrust of the government and even healthcare entities in BIPOC, low-income and immigrant communities. Adding to that are concerns about the safety of the vaccine due in large part to misinformation, making these communities understandably hesitant to be vaccinated.[5]

Additionally, there are registration hurdles. Many in historically underserved communities do not have established relationships with health providers, a factor upon which current registration systems rely heavily. Many underserved communities do not have reliable access to a smart phone or computer and lack the “tech savviness” to navigate website registration. Content is often offered only in English, and most available appointments are during the traditional workday. Many vaccination opportunities are at sites that are difficult to get to, particularly for those in jobs without “PTO” or “sick time” or individual means of transportation. Given the greater incidence of side effects from the second dose of vaccine, some people choose not to receive the dose due to fears of missing work and subsequently losing their jobs.

Finally, there are the normal logistical challenges that every mass vaccine clinic faces:

- highly variable delivery time and quantity of vaccine,

- finding suitable spaces to support mass vaccination events,

- creation and execution of inclement weather plans,

- administrative, billing and IT burdens,

- balancing the use of staff for vaccine deployment while simultaneously providing ongoing routine care to patients, and

- no guarantee of reimbursement for vaccine administration.

Additionally, we are operating under an ever-changing Statewide Vaccine Distribution Plan that adds new population eligibility as vaccination milestones are achieved and we must be agile enough to quickly respond to short-notice openings of new phases.

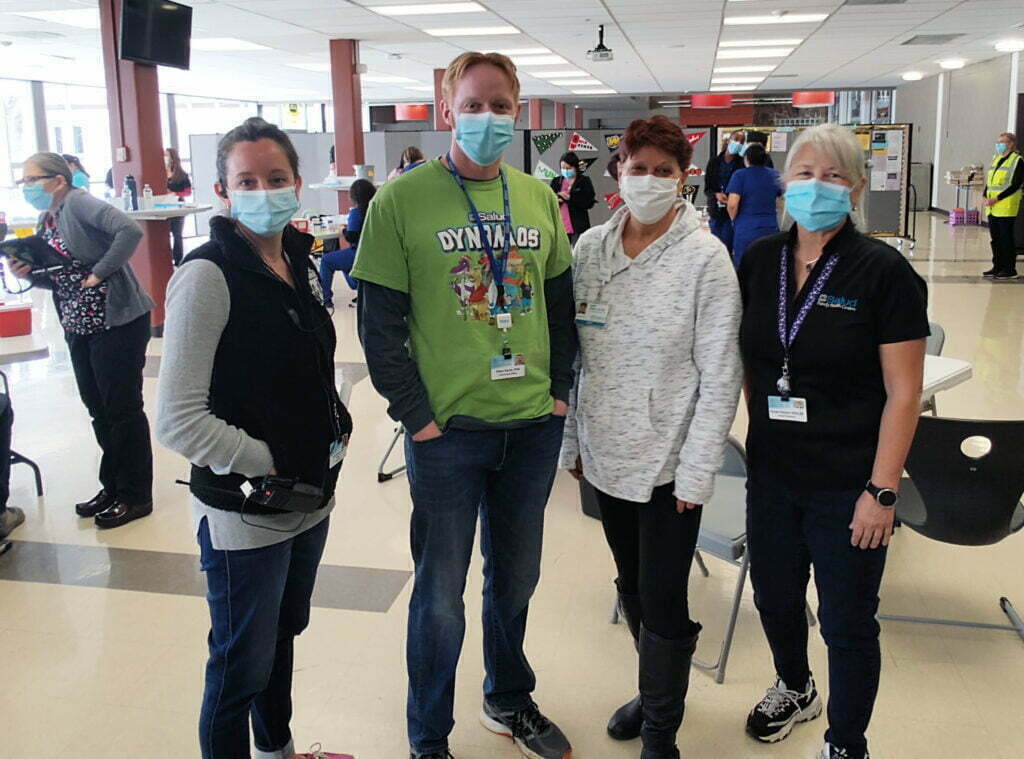

Dr. Leah Schulz (left), Dr. Ethan Kerns, Debby Myers, R.D.H., and Sue Hanson, R.D.H.

Salud has been working to overcome these challenges through our community-based “pop-up” vaccine clinics. We’ve collaborated for months with BIPOC organizations, employers and leaders; non-profits; the media; local churches; elected officials; other healthcare agencies; hospital systems; and even local counties and public health departments in some cases to facilitate and encourage cooperative community-led vaccination efforts. We’ve relied on the existing, trusted relationships people have with community-based organizations, and asked those organizations to guide the outreach while we support the vaccine education and administration piece. We’ve asked for their support in helping their clients register for appointments when needed. We’ve also offered bilingual registration on the phone and online and arranged for clinics at various days and times throughout the week and on weekends.

We have run several successful mass vaccination “pop-up” clinics and are now preparing to offer more routine community-based vaccine clinics in many areas across the state in the coming months. It’s an “all hands-on deck” approach, and dental teams will play a major role.

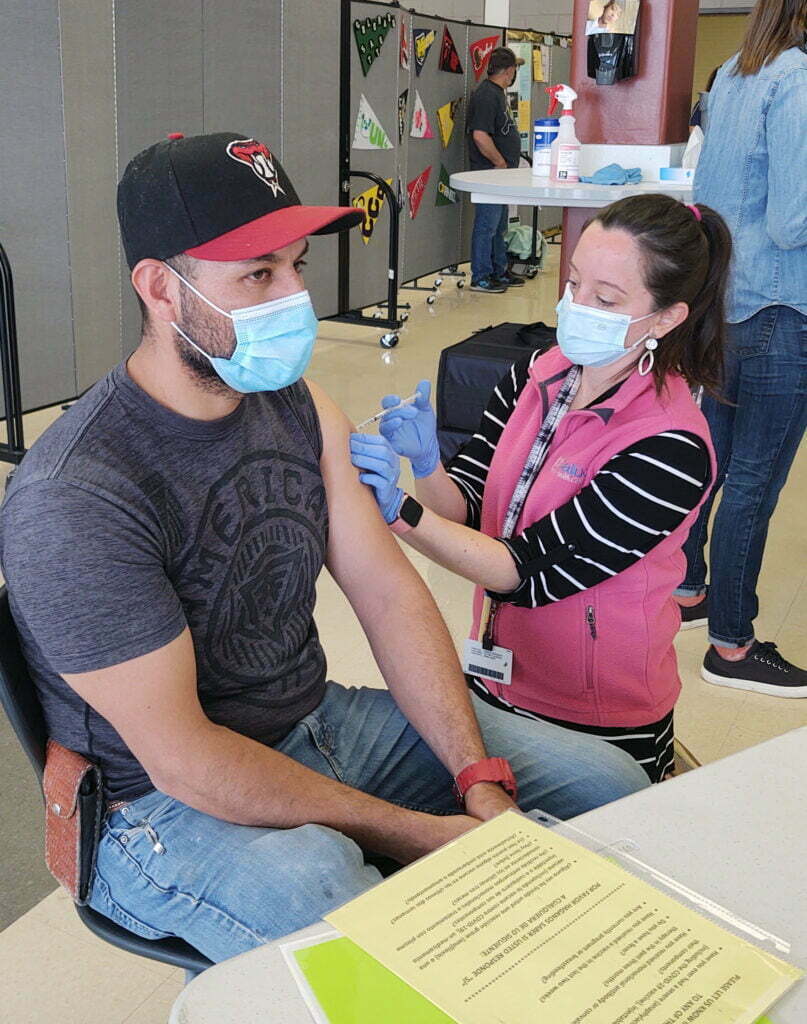

Salud has adopted a truly interdisciplinary approach to the vaccine effort: we’ve enlisted our entire dental team! Most of our dental assistants are crossed-trained to screen patients for COVID-19 symptoms, take temperatures, talk about vaccine safety, and answer patient questions. Many of our hygienists and dentists received training from our medical colleagues and now draw and/or administer the vaccine under their supervision. At the time this article was written, in mid-March, Salud Family Health had administered 45,752 doses of the vaccine. Of that amount, Salud dentists and dental hygienists had administered over 450 doses of the vaccine. All the while, our dental departments have remained open to provide routine comprehensive care.

Dentists in all practice models have a mission-critical function to help achieve herd immunity. We can listen to and talk with our patients about their vaccine-related concerns and challenges. For example, one Latinx woman told me that she wouldn’t get the vaccine because she heard on Facebook that it will make her infertile. I acknowledged that if her understanding of the vaccine side effects were true, I could certainly see how this would deter her. We talked about what other information sources she might consider before definitively making her decision to be vaccinated or not. She stated that she trusted her doctor and me; so together we addressed her vaccine concerns and, after reassuring her that no scientific evidence supports the infertility claim, she registered for the vaccine.

If you aren’t already, please consider including the COVID-19 vaccine in your routine dental visit discussions over the next few months. You never know the impact one conversation from a trusted health professional can have that could help someone make a decision that could save his or her life.

Like many other FQHCs, Salud is committed to vaccinating our communities, as that is what is most needed right now. I’m proud that our organization continued our practice of integrated healthcare by including dentists and their teams in the vaccination effort. If you or your team are interested in helping, please consider volunteering with organizations who provide vaccination clinics, including Salud (saludclinic.org). We’re all in this together.

Leah Schulz, D.D.S., is the director of dental projects and a general dentist at Salud Family Health Center. She is a member of the CDA Board of Trustees, a member of the CDA Government Relations Council, a member of the CDA Membership Council, a CODPAC board member, and a delegate to the American Dental Association. She earned her dental degree from the University of Colorado School of Dental Medicine, where she now serves as adjunct faculty. Contact her at lschulz@saludclinic.org.

[1] Equity in Vaccination: A Plan to Work with Communities of Color Toward COVID-19 Recovery and Beyond, https://www.centerforhealthsecurity.org/our-work/pubs_archive/pubs-pdfs/2021/20210209-CommuniVax-national-report.pdf, Accessed March 7, 2021

[2] Risk for COVID-19 Infection, Hospitalization, and Death By Race/Ethnicity, https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/covid-data/investigations-discovery/hospitalization-death-by-race-ethnicity.html, Accessed March 7, 2021

[3] American Life Expectancy Dropped By A Full Year In 1st Half Of 2020, https://www.npr.org/2021/02/18/968791431/american-life-expectancy-dropped-by-a-full-year-in-the-first-half-of-2020, Accessed March 1, 2020

[4] Reckoning with Histories of Medical Racism and Violence in the USA, https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(20)32032-8/fulltext, accessed March 1, 2020

[5] Vaccine Monitor: Nearly Half of the Public Wants to Get a COVID-19 Vaccine as Soon as They Can or Has Already Been Vaccinated, Up across Racial and Ethnic Groups Since December, https://www.kff.org/coronavirus-covid-19/press-release/vaccine-monitor-nearly-half-of-the-public-wants-to-get-covid-19-vaccine-as-soon-as-they-can-or-has-already-been-vaccinated-up-across-racial-and-ethnic-groups-since-december/ Accessed March 7, 2020