Dr. Bethany Valachi, P.T., D.P.T., M.S., C.E.A.S.

From the Spring/Summer 2020 Journal of the Colorado Dental Association

With the development of the COVID-19 pandemic, a new layer of stress and physical challenge is added to the problem of work-related pain in dentistry. Personal protective equipment, distancing and controlling the environment all contribute to mental stress, which research shows can lead to physical pain.

Now, more than ever, dental professionals need to be availing themselves of evidence-based ergonomic and wellness education. Pain is not a necessary by-product of dentistry. You can reduce or eliminate your pain with targeted, evidence-based interventions. Unfortunately, many dental and hygiene schools do not teach comprehensive evidence-based ergonomic and wellness education. Also, many dental equipment manufacturers offer non-ergonomic equipment that can actually create pain syndromes. Additionally, the dental continuing education system is becoming flooded with sponsor-driven free lectures that bias their message. Is it any wonder that:

- 75% of dental professionals complain of musculoskeletal pain1

- One-third of dentists who retire early are forced to, due to a musculoskeletal disorder2,3

- And the prevalence of lower back pain today (67%) is the same as it was in 1946?1,4

For a dentist, retiring only 10 years early can lead to a loss of $1M-$2M. The financial impact of poor ergonomics (forced early retirement, employees’ workers compensation claims, training new employees, sick leave and healthcare expenses) can lead to a financial crisis.

Resolving the Pain Problem

So why has the prevalence of pain in dentistry not improved over a 70-year period? The answer is two-fold:

- The etiologies have not been correctly identified.

- Interventions and product development are frequently not evidence based.

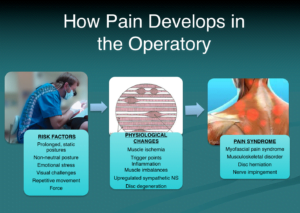

Without accurate recognition of the etiology, it is impossible to implement effective interventions. Dentists would not dream of treating a patient without first identifying the problem or cause of the patient’s pain. Likewise, identifying the etiologies of work-related pain in the operatory is the first step in determining effective interventions.5 There are numerous personal risk factors outside the operatory, however it is the risk factors inside the operatory that are the greatest culprits leading to the demise of dental professionals’ musculoskeletal health. These risk factors, in turn, lead to physiological changes in the body.

Figure 1: How pain develops in the dental operatory.

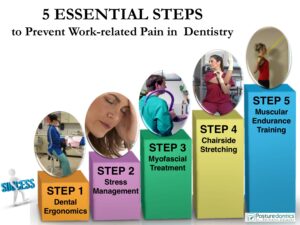

The proper sequence to implement these evidence-based interventions is critical to your success in preventing and resolving pain. It is all too common to observe dental professionals attempting to resolve their pain with special therapies, medications, or exercise routines, only to return to the operatory environment that likely caused the pain problem in the first place! Therefore, dental ergonomic intervention is first and foremost.

Figure 2: The 5 Essential Steps to Prevent Work-Related Pain in Dentistry. The sequence that interventions are implemented is critical to your success.

Step 1: “Ergonomize” Your Operatory

Imagine spending $1,500 on a pair of dental loupes, only to discover they actually exacerbate your neck pain. An investment in non-ergonomic equipment can result in two poor options: live with the potentially damaging consequences or spend additional money on more equipment—neither is a good option.

Some important questions to consider:

- What type of operator stool should I select based on my height, lumbar curvature, gender and body size?

- How can I economically make ergonomic modifications to my operatory?

- What style of backrest is best for preventing back pain?

- Is my loupe declination angle improving or hurting the health of my neck?

- How can I easily maintain optimal posture while treating the upper arch?

- Do certain delivery systems promote movement that leads to shoulder pain?

- Can certain types of instruments and hand pieces help prevent hand pain?

- What is the best clock position to treat certain tooth surfaces?

Figure 3: Correcting poor operatory ergonomics should be your first course of action in resolving work-related pain.

For example:

One of the most common ergonomic errors I observe is dental professionals wearing through-the-lens (TTL) loupes with a poor declination angle that causes severe forward-bending of the neck greater than 20°, which can lead to neck pain.10,11 I have found only one style of loupes that consistently keeps operators in a safe head posture.

Step 2: Down-Regulate Your Sympathetic Nervous System

Since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, you may have noticed increased tension or pain in your neck and lower back. Why? Research shows that these are two areas especially responsive to emotional stress. From our earliest hunter-and-gatherer days, we are still hard-wired for the fight-or-flight response (via the sympathetic nervous system), which preferentially shunts blood from the small postural muscles in the neck and low back to the larger “mover” muscles in the arms, legs, hips and shoulders. This response may have proven life-saving thousands of years ago but may not serve you as well in a stressful COVID environment today! When your nervous system is in overdrive, the small postural stabilizing muscles are not “as important” as the larger mover muscles and become deprived of oxygen, ischemic and painful. Dental professionals must employ specific evidence-based strategies that down-regulate the sympathetic nervous system and prevent stress-induced pain syndromes.

For example:

Shallow “chest breathing” is a common breathing pattern in the dental operatory, which deprives postural muscles of oxygen. Shallow breathing can up-regulate your sympathetic nervous system (fight-or-flight response), heightening your body’s stress response.12,13 Lower back and sacro-ioliac pain can also result from sub-optimal breathing patterns.14

Step 3: Self-treat Your Myofascial Pain

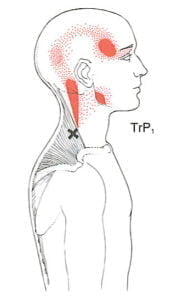

Have you ever experienced a headache behind your eye that doesn’t resolve with pain medication? It’s possibly referred from trigger point #1 in your upper trapezius muscle. Trigger points refer pain to a distant area of the body and are common among dental professionals due to body asymmetry, poor postures, poor body mechanics, repetitive movement, lack of movement, sustained muscle contraction and mental stress. Unfortunately, the impact of trigger points is often misunderstood or overlooked and dental professionals may be sent from specialist to specialist with no resolution to their pain. It is important to identify and relieve trigger points as soon as possible to restore nutrient flow to the muscle, prevent muscle imbalances and prevent compression on nerves. Strengthening muscles with unresolved or active trigger points will often make your pain worse, which is why this is Step 3 in the sequence.

Figure 4: A common trigger point among dental professionals refers a “headache behind the eye.”

For example: Trigger points in the scalene muscles (neck) are common among dental professionals, and typically refer pain to the medial border of the shoulder blade.15,16 However, unless a massage therapist is specially trained in trigger point therapy, they will usually apply massage to the point where pain is reported, not the source of the pain.

There are various methods to treat trigger points, but due to costs, time constraints and convenience, self-treatment is often the most practical and economical consideration. One effective technique is to deactivate trigger points using a specific 5-step protocol with a Backnobber tool.17

Step 4: Develop Good Flexibility

Have you noticed you are tighter on one side than the other? Muscle imbalances are very common among dental professionals and can lead to neuromuscular, joint and spine disorders.

Chairside stretching can help correct these imbalances, restore full range of motion, and safely prepare your muscles for strengthening. Muscles must be stretched properly, because over stretching muscles with active trigger points may cause micro-tearing of muscle, which is why stretching is recommended after trigger point treatment.

Since dental professionals are prone to muscle imbalances, it is important to ensure you are targeting the correct muscles with your stretching. Rather than stretching muscles that are already elongated (as some yoga regimens do), focus on the muscles that tend to become short, tight and is chemic when practicing dentistry. Chairside stretches are especially important for men, who are more prone to musculoskeletal injury due to poor flexibility than women.

Figure 5: Chairside stretching is an essential intervention to control work-related pain.

For example: Tight chest (pectoralis muscles) and scalene muscles are very common among dental professionals and can compress the brachial plexus, causing arm and hand pain and numbness—mimicking carpal tunnel syndrome.16,18

Step 5: Strengthen Specific Stabilizing Muscles

Have you ever hired a personal trainer or started a Pilates or Crossfit routine only to find your pain did not improve or even got worse? Because dental professionals are prone to unique muscle imbalances, exercises that are not a problem for the general public can throw them into “the vicious pain cycle.” This is why all strengthening exercise is not necessarily good exercise for dental professionals. If you strengthen the wrong muscles, or muscles with active trigger points, your pain may worsen. This is critical to understand, and why strengthening is the fifth step in the sequence. You must avoid strengthening programs until the area is pain-free and you have full-range of motion.

Figure 6: Research shows muscular endurance training of the lower trapezius can help reduce neck pain.

Studies show that dentists who have better endurance of the back and shoulder girdle muscles have less musculoskeletal pain.19,20 Because of their vulnerability to muscle imbalances, the exercise needs of dental professionals are very specific, and while certain key muscle groups should be targeted, others should be very cautiously approached or avoided altogether in an exercise regimen.

For example:

Strength training the upper trapezius muscle is one of the fastest ways dental professionals can develop, perpetuate or worsen neck pain! The upper trapezius muscle is the most actively used muscle in dentistry and also the most vulnerable to pain. It easily develops a painful ischemia, so performing anaerobic heavy resistance exercise on it is inappropriate for dental professionals. In the dental operatory, your postural muscles contract at low levels for extended time periods, which is why endurance-style training is imperative to prevent injury in dentistry. When your postural “stabilizer” muscles become fatigued, not only can the operator slump into less than optimal posture, but the “mover” muscles now must perform a stabilizing task for which they are not designed. The resulting muscle imbalances can cause painful trigger points and/or muscle spasms to develop in the inappropriately used muscle. Over time, these imbalances in dental professionals may ultimately lead to a musculoskeletal disorder. Multiple studies support muscular endurance-type training (not strength training) as the foundation of a successful exercise program for dental professionals.19,20

Conclusion

It cannot be overstated that implementing only one or even a few of the above steps is unlikely to fully resolve pain syndromes. Your ability to practice dentistry pain-free-involves addressing numerous risk factors with proven, evidence-based strategies.

hany Valachi, P.T., D.P.T., M.S., C.E.A.S., is the author of the book, “Practice Dentistry Pain-Free,” a clinical instructor of ergonomics at OHSU School of Dentistry in Portland, OR, and is recognized internationally as a dental ergonomics expert. She is CEO of Posturedontics, a company that provides evidence-based dental ergonomic education and evaluates dental equipment. She has published more than 80 articles in peer-reviewed dental journals and offers dental ergonomic educational materials on posturedontics.com. Contact her at info@posturedontics.com.

References:

- Moodley R, Van Wyk JM, Naidoo S. The prevalence of occupational health-related problems in dentistry: A review of the literature. J Occup Health. 2017 Dec 6. doi: 10.1539/joh.17-0188.

- Ergonomics and Dental Practice: Preventing work-related musculoskeletal problems. Nov 01, 2014. ADA Professional Product Review. http://www.ada.org/en/publications/ada-professional-product-review-ppr/archives/2014/november/ergonomics-and-dentalpractice-preventing-work-related-musculoskeletal-problems. Accessed 12/18/2017.

- Burke FJ, Main JR, Freeman R. The practice of dentistry: an assessment of reasons for premature retirement. Br Dent J 1997;182(7):250-4.

- Biller FE. Occupational hazards in dental practice. Oral Hyg 1946;36:1994.

- Valachi B, Valachi K. Mechanisms leading to musculoskeletal disorders in dentistry. JADA. 2003;1344-1350.

- Valachi B. Practice Dentistry Pain-free: Evidence-based Strategies to Prevent Pain and Extend your Career. Portland, Oregon: Posturedontics Press; 2008:5.

- Llamas-Ramos R, Pecos-Martin D, Gallego-Izguierdo T, et al. Comparison of the short-term outcomes between trigger point dry needling and trigger point manual therapy for the management of chronic mechanical neck pain: A randomized clinical trial. J Orthop Sport Phys. 2014; 44:852-862.

- Ziaeifar M, Arab AM, Karimi N, Nourbakhsh MR. The effect of dry needling on pain, pressure pain threshold and disability in patients with a myofascial trigger point in the upper trapezius muscle. J Bodyw Mov Ther. 2014;18(2):298-305.

- Abbaszadeh-Amirdehi M, Ansari NN2, Naghdi S, Olyaei G, Nourbakhsh MR3Neurophysiological and clinical effects of dry needling in patients with upper trapezius myofascial trigger points. J Bodyw Mov Ther. 2017;21(1):48-52.

- Andersen JH, Kaergaard A, Mikkelsen S, et al. Risk factors in the onset of neck/shoulder pain in a prospective study of workers in industrial and service companies. Occup Environ Med. 2003;60(9):649–54.

- Ariens GA, Bongers PM, Douwes M, et al. Are neck flexion, neck rotation, and sitting at work risk factors for neck pain? Results of a prospective cohort study. Occup Environ Med. 2001;58(3):200-7.

- Shahidi B, Haight A, Maluf K. Differential effects of mental concentration and acute psychosocial stress on cervical muscle activity and posture. J Electromyogr Kinesiol. 2013;23(5):1082-9.

- Jerath R, Crawford MW, Barnes VA, Harden K. Self-regulation of breathing as a primary treatment for anxiety. Appl Psychophysiol Biofeedback. 2015;40(2):107-15.

- Boyle KL, Olinick J, Lewis C. The value of blowing up a balloon. N Am J Sports Phys Ther. 2010;5(3):179-88.

- Ferguson LW, Gerwin R. Clinical Mastery in the Treatment of Myofascial Pain Lippincott Williams and Wilkins, Baltimore, 2005.

- Travell JG, Simons DG, Simons LS. Myofascial Pain and Dysfunction: The Trigger Point Manual, Vol. 1. Baltimore, Maryland: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 1999:111,179-87.

- Hanten W, Olson S, Butts N, Nowicki A. Effectiveness of a Home Program of Ischemic Pressure Followed by Sustained Stretch for Treatment of Myofascial Trigger Points. Physical Therapy 2000:80;997-1003.

- Doneddu PE, Coraci D, De Franco P, Paolasso I, Caliandro P, Padua L. Thoracic outlet syndrome: wide literature for few cases. Status of the art. Neurol Sci. 2017 Mar;38(3):383-388.

- Lehto TU, Helnius HY, Alaranta HT. Musculoskeletal symptoms of dentists assessed by a multidisciplinary approach. Community dentistry and oral epidemiology 1991; 19:38-44.

- Rundcrantz B, Johnsson B, Moritz U. Occupational cervico-brachial disorders among dentists. Swedish Dental Journal 1991; 15:105-115.