By Scott Hamilton, D.D.S., Assistant Professor in Pediatric Dentistry, Children’s Hospital Colorado

From the Summer 2018 Journal of the Colorado Dental Association

Early childhood caries (ECC) is the most common preventable health condition in U.S. children. Severe early childhood caries (S-ECC), formerly referred to as baby bottle tooth decay, remains a public health challenge for dentists and pediatric dentists alike. A “disease of poverty,” S-ECC occurs most frequently in low socioeconomic populations. It causes a diminished oral health-related quality of life for the countless children who experience dental infections, missed school days, emergency room visits and operating room visits. It costs Colorado families and taxpayers tens of millions of dollars annually. It also predicts for higher future dental caries rates in both primary and permanent dentitions.1

IMAGE 1

Management of S-ECC is difficult for multiple reasons. S-ECC progresses rapidly and can cause pulpal inflammation or infection of primary incisors in a matter of months (Image 1). Very young patients can have multiple surfaces of decay on multiple teeth while at a pre-cooperative age, necessitating the use of medical immobilization (papoose board,) sedation or general anesthesia. The associated costs of these options can be prohibitive for many families, especially those of low socioeconomic status. Parents often have high esthetic expectations for their children’s primary maxillary incisors. The most esthetic restorative options for primary incisors are highly technique-sensitive and many general dentists are unlikely to offer them.2

Each of the restorative options currently used has at least one disadvantage.

- Composite resin strip crowns are the most technique sensitive restorations. They demand patient cooperation and excellent hemorrhage control. Traditional composite resin strip crowns require preparation of teeth for full coverage crowns by reducing all surfaces by roughly 1 mm. After etching and bonding the remaining enamel and dentin, a cellulose crown form filled with composite resin is positioned onto the prepared tooth. After light curing, the crown form is removed; leaving behind a full coverage bonded (not cemented) restoration.

- Pre-formed zirconia crowns and stainless-steel crowns with resin facings offer very good esthetics but, like composite resin strip crowns, necessitate a high degree of cooperation that may only be possible in an operating room setting. In addition, they require removal of the most tooth structure, occasionally even resulting in iatrogenic pulpal exposures.3 In contrast to strip crowns, these crowns are luted with a cement such as Fuji IX or Ketac.

- Silver diamine fluoride has increased in popularity due to its capacity to arrest the caries process, but by definition is not a restoration. It is also not readily accepted by many parents due to the resulting permanent black discoloration, especially in the maxillary anterior region.4

- Interim therapeutic restorations or ITRs (sedative fillings) have poor retention rates and high frequency of recurrent decay, especially in multi-surface carious lesions.5

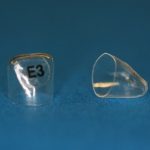

IMAGE 2 Success Essentials cellulose strip crowns (smlglobal.com/pediatric-strip-crowns-anterior). Several sizes are available, shown is the primary maxillary right central incisor size 3 crown form.

Hall Technique for Incisors

One simple and effective option for restoring primary molars affected by early childhood caries is known as the Hall Technique. This procedure calls for stainless steel crowns to be cemented directly onto carious teeth with little to no tooth preparation or caries removal.3 Until recently, no similar option was available for primary incisors.

Glass Ionomer Strip Crowns for Incisors

A novel approach to restoring incisors afflicted with S-ECC using glass ionomer strip crowns (Image 2) first appeared in the literature in 2013. Like the Hall Technique, this option requires almost no tooth preparation. It can be accomplished in a few minutes. The results are esthetically acceptable. The affected teeth gain the benefits of full crown coverage as well as the benefits of glass ionomer such as direct bond of restorative material to tooth structure and caries arrest. 6

Glass ionomer strip crowns have been completed on over 100 carious primary incisors in the Children’s Hospital Colorado Pediatric Dental Residency over the past 24 months. To date, there is only one known failure, and a review of the radiograph in that case indicates a nearly hopeless prognosis for that tooth before the restoration was attempted. More research will be conducted to compare glass ionomer strip crowns to composite resin strip crowns and to traditional Class III, Class IV and Class V ITRs.

Case Presentation

Patient MW (age 2 years, 6 months) presented in December 2016 with caries on teeth E, F and S (Image 3). It was decided to restore all three teeth in one visit with the use of medical immobilization. No local anesthetic was given. The patient’s behavior was very uncooperative at both her initial visit and her treatment visit. A Class I glass ionomer was placed on tooth S. Teeth E and F were restored with glass ionomer strip crowns. The treatment time was 15 minutes, including the time lost to intraoral photography.

IMAGE 3 Pre-operative image.

Using a high-speed handpiece and a narrow diamond bur, the interproximal areas were slightly opened (Images 4 and 5). This step is not necessary if adequate interproximal space is present. Note: No incisal, facial or lingual reduction was completed.

IMAGE 4 IMAGE 5

Next, the appropriate size crown forms were chosen. The cervical margin fit snugly against the tooth; the width of the crown form approximated the original contours of the tooth; and the completed lingual surface did not interfere with occlusion (Images 6 and 7).

IMAGE 6, IMAGE 7

Caries removal was completed with a slow speed handpiece and a small round bur, but initial results indicated that this step may not be necessary. GC cavity conditioner (Image 8) was applied to all surfaces of teeth E and F for 30 seconds (Image 9), followed by rinsing and drying for 30 additional seconds (Image 10). Because the restoration material is glass ionomer and not composite, it is not necessary to desiccate the teeth or to use bond agent.

IMAGE 8

GC Cavity Conditioner.

IMAGE 9 Condition for 30 seconds

IMAGE 10 Rinse and dry, but do not desiccate

Next, the crown forms were filled with a resin modified glass ionomer (Fuji II LC) and positioned on the teeth. After light curing for three seconds, the bulk of excess material was removed with an explorer (Image 11). The restorations were then cured 20 seconds each facially and lingually (Images 12 and 13).

IMAGE 11, IMAGE 12, IMAGE 13

The strip crown forms were removed with an explorer, taking care not to gouge the newly placed restorations (Image 14). Despite fully light curing the material, the chemical cure of resin modified glass ionomer is not complete for several hours.

IMAGE 14

Refining with a carbide finishing bur was completed to level the incisal edges and adapt the margins (Image 15).

IMAGE 15

IMAGE 16 Final restorations, immediately after placement.

The patient returned to the clinic for a recall exam 16 months later, at which time the restorations were intact. No appreciable wear or recurrent decay were noted; the patient reported no pain or sensitivity; and the periodontal health appeared normal (Images 17 through 20).

IMAGE 17, IMAGE 18

IMAGE 19 Occlusal radiographs, pre-operative.

IMAGE 20 Occlusal radiographs, 16-month post-operative.

To fully endorse glass ionomer strip crowns, more research is needed to evaluate long-term results compared to traditional restorations. The initial results give reason for optimism. Parents are pleased with the esthetics, there has been a very low failure rate to date, and many general anesthetic or conscious oral sedation visits have been averted.

Photo credits: David Burke, D.M.D. and Megan Su, D.M.D.

References:

- AAPD Oral Health Policies: Policy on Early Childhood Caries (ECC) Classifications, Consequences, and Preventive Strategies. Reference Manual 2017-8. Pediatr Dent 2017; V39(special issue): 59-61.

- AAPD Oral Health Policies: Reference Manual 2017-8. Policy on Early Childhood Caries (ECC): Unique Challenges and Treatment Options. Pediatr Dent 2017; V39(special issue): 62-3.

- AAPD Oral Health Policies: Reference Manual 2017-8. Best Practices in Pediatric Restorative Dentistry. Pediatr Dent 2017; V39(special issue): 312-324.

- AAPD Clinical Practice Guidelines: Reference Manual 2017-8. Use of Silver Diamine Fluoride for Dental Caries Management in Children and Adolescents, Including Those with Special Health Care Needs. Pediatr Dent 2017; V39(special issue): 146-155.

- AAPD Oral Health Policies: Reference Manual 2017-8. Policy on Interim Therapeutic Restorations (ITR). Pediatr Dent 2017; V39(special issue): 57-58.

- An improved interim therapeutic restoration technique for management of anterior early childhood caries: report of two cases. Nelson T. Pediatr Dent. 2013 Jul-Aug;35(4):124-8.